752nd Tank Battalion in the

Battle at "The Rock"

- Researched and Written by Robert Holt -

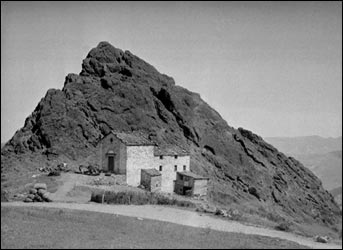

The 752nd Tank Battalion's C Company won a commendation from the 85th Infantry Division for “heroic action in combat” on 26-27 September 1944, at a place the tankers called “The Rock.” To the local inhabitants, this place was better known as Sasso di San Zenobi (The Rock of Saint Zenobi). Before the war, a church and a few small buildings were nestled next to this outcropping, as shown in the 1939 photo shown above. The Germans used these buildings in their defense of Hill 966.

From a geological perspective, The Rock is a black and greenish Serpentinite outcropping near the crest of Hill 966. Unlike the rocks of the surrounding area, it is of volcanic origin. The Rock is believed to be a fragment of the oceanic crust that was upheaved when the European and African tectonic plates collided during the Upper Cretaceous age. This collision formed the Apennine Mountains, which originally had been at the bottom of an ancient ocean during the Middle Upper Triassic Period.

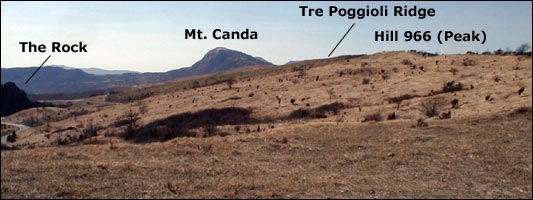

The Rock sits near the crest of Hill 966, which is more properly known as Tre Poggioli. Hill 966 is a smooth-sloped, inhospitable hill mass, some 3,168 feet in height, that extends northeast from the base of Mt. Canda.

On 26 September 1944, the 752nd was called upon to support the 85th Infantry in an attack against Tre Poggioli, where stubborn defenders of the German 362nd Grenadiers were well dug-in. The general objective was to bypass the heavily defended and more strategic Mt. Canda and seize Hill 966. Once accomplished, the 85th was to regroup and take the much more rugged Mt. Canda, which was to the southwest of Tre Poggioli.

The 752nd’s attack on Tre Poggioli was launched from Collinelle at 0800 hours on 26 September. Company C carried out the main attack in support of the 1st Battalion of the 338th Infantry Regiment as well as the 1st Battalion of the 339th. Company B participated in an overwatch role. A steady rain fell over the battlefield.

The Germans had quickly established their center of resistance in Sambuco, a small village of thick-walled houses nestled in some craggy hills south of the Tre Poggioli ridge. The tank-infantry force met stiff opposition from small arms, mortar, and artillery barrages, which were directed by observation posts established on the Ravignana Heights to the north. Throughout the day, Companies B and C fired on enemy troops along the Tre Poggioli ridge between Mt. Canda and Hill 966, inflicting heavy casualties and destroying one self-propelled gun (SPG). Their advance was slowed not only from the heavy fire that was directed upon them, but also by antitank minefields. By nightfall, they had succeeded in taking the tiny villages of Caburaccia and Sambuco, representing a total gain of just over 300 yards for the day. The tanks had reduced the town of Sambuco to rubble in the fighting.

At 0530 hours the next morning (27 September), one platoon of tanks from A Company joined in the action and provided overwatch support from Peglio and Collinelle. B Company once again supported C Company’s renewed attack by providing direct fire support from the Tre Poggioli ridge, and by directing three fire missions of the Assault Gun Platoon. Tanks from HQ joined the C Company tankers in the attack.

The 752nd tanks fired machine guns and high explosive (HE) shells at close range in an attempt to dislodge the enemy. The Germans responded with heavy small arms and mortar fire from the hill itself, and from the higher ground to the west and south. In addition, they made good use of their 75 and 105mm SPGs.

In typical “lead by example” style, Major Woodbury took his 76mm M4A3 tank to join in the assault. During the mid-morning, they advanced slowly toward The Rock, firing at the German machine gun emplacements as they went. A heavy artillery barrage suddenly rained down on the tankers. The ground began erupting all around the tankers, showering dirt and shrapnel everywhere. Suddenly the Major’s tank was rocked by a blinding flash and a tremendous explosion. The right side of the turret had been struck by a 105mm shell from a hidden StuG III SPG of the StuG Brigade 907. Observers in the following tank say the Major’s tank was totally obscured by smoke and dust for several seconds.

No one was hurt in the blast, although it did cause the Major to lose his chewing tobacco. Although no major damage was done, the blast knocked out the turret's power traverse mechanism. However, the turret could still be traversed at least slowly by using the hand crank. The tankers knew that this was a serious liability going up against hidden SPGs at close range. But they continued on, moving across a flat area and knocking out gun emplacements at point blank range. The heavy artillery barrage continued, and the 85th Infantry finally requested that the tanks leave the area, as they were drawing far too much fire.

As the Major’s tank came out of a draw, they kept a close watch on The Rock and the church, since German tanks and SPGs had been spotted behind both. They moved parallel to the ridge, from right to left in the photo at the top of this web page. Knowing that German armor was using the church for cover, the tankers had hand-cranked their turret roughly 45 degrees to the right in anticipation. Suddenly, a 105mm German StuG III SPG emerged from a small area between The Rock and the church. The Major’s tank was now crossing directly into its field of fire at close range.

Harold White, the assistant gunner, yelled “Tank!”, and Major Woodbury calmly said “Let’s go!” to his crew over the tank’s intercom. With a round of HE (High Explosive) already in the breech, the gunner Bill Cardone laid the main gun on the target as best he could, and with his Sherman still moving, he hastily sent the round on its way. The HE round hit the front of the StuG, but merely cracked the armor without penetrating it. White quickly loaded a round of AP (Armor Piercing), while the driver Howard Stine boldly stopped the tank to allow a better shot. Cardone fired again, and this round found its mark with devastating results. The round entered the front of the SPG and went clear through the rear, causing a tremendous explosion. The StuG III burst into flames.

In the photo below, a B Company tanker poses in front of the destroyed 105mm StuG very soon after it was knocked out. The entry hole made by the AP shell can be clearly seen on the front glacis plate. Two other hits can also be seen. One is on the lower edge of the front glacis plate, and the other is on the gun mantlet. The commander’s cupola and armor plating lie askew in the front of the SPG, while a road wheel rests upright several feet to the vehicle’s right side (left side of the photo).

The following after-action photo more clearly shows the damage that was done to the StuG III. The devastation to the vehicle’s left side and rear was catastrophic. Engine compartment components such as the cooling fan and radiator lie far behind the StuG. This photo shows that this vehicle used waffle-pattern Zimmerit anti-magnetic coating, and had a Topfblende cast (rounded) gun mantlet and metallic return rollers characteristic of the late version of the StuG III Ausf. G.

By 1100 hours, some of the German infantry were seen advancing to the north, apparently fearing that they were about to be cut off. With that, the 85th Infantry stormed up the hill, coming under heavy machine gun and artillery fire from Mt. Canda’s northern slopes to their rear. Shortly after noon, the 752nd and 85th had driven all of the defenders off Hill 966. During the night of 27-28 September, the Germans withdrew from Mt. Canda under the cover of darkness and heavy rain. The heavy rain over the next several days made the roads and hills too impassable for the tanks to pursue.

As always, the 752nd paid a price for the victory at Hill 966. On 27 September, the tanks of C Company were engaged in a mission of holding the hill until the Infantry could move up. Sergeant Ned O'Neill, a tank commander, received radio orders to move his tank into a position from which he could direct fire into enemy foxholes and machine gun positions, and overwatch the movement of the remaining tanks. Sergeant O'Neill worked his tank up to the very crest of the ridge, and as he teetered on an almost vertical drop, he spotted a column of German artillery pulling out of the draw below. Sergeant O'Neill's gunner could not fire upon them, since he could not depress his main gun enough to take the shot. Major Woodbury called for his own artillery to fire a maximum distance smoke marker, but since it fell short of the Major's position the U.S. artillery also could not fire upon the retreating Germans.

Sergeant O'Neill began backing his tank off the ridge over extremely rough and muddy terrain, while under heavy artillery, mortar, machine gun, and sniper fire. As the tank backed up, Sergeant O'Neill for some unknown reason ordered his driver to make a hard right turn, which caused the tank to partially throw one of its tracks. Despite the heavy fire, Sergeant O'Neill immediately started to dismount from his tank to try to direct his driver to run the track back on the suspension. But as he lifted himself out of the turret, Sergeant O’Neill was immediately hit by machinegun fire. He dropped back into the safety of his own tank, where his loader administered a shot of morphine. Although a medic made it to the tank, Sergeant O'Neill's wounds were too severe, and he died a few minutes later on the turret floor. After the infantry secured Hill 966, Ned O'Neill's crew removed him from the tank, covered him with a tarp, and slowly carried him down the hill to a waiting jeep ambulance.

Sergeant O'Neill was posthumously awarded the Silver Star for "his gallant action above and beyond the call of duty." Three other C and A Company men were wounded in action on 27 September, and Major Woodbury had been wounded the day before at the onset of the battle.

Of course, the small village near Sasso di San Zenobi was never the same after the fighting. The church, as well as a nearby house the GIs called "The Casa", were heavily damaged. Although they survived the war, they were finally torn down some years later, and have not been replaced. The damage to the church can be seen in the after-action photo below. The tanker in the photo is Cpl. George Blessing, the gunner in Tank # 15 of B Company’s 3rd Platoon. Cpl. Blessing later became the 752nd’s last combat fatality of the war.

The years that followed were far more peaceful. In 1990, segments of an Italian movie called "La settimana della Sfinge" were filmed at The Rock. It was a love comedy, in which a simple-minded waitress falls in love with a philandering television repairman. Buildings at the nearby dairy farm were converted into a truck driver’s restaurant for the movie. A false gas station was built at the very spot where “The Casa” once stood. Many B Company men will remember The Casa as a bombed out building that they used for shelter during the weeks that followed the battle.

Today, Sasso di San Zenobi is a peaceful place, and is currently the site of a large sheep, goat, and horse farm that is locally famous for its fine cheeses. The hill at the base of Sasso di San Zenobi is now a great spot for picking mushrooms. The area is still under guard, but instead of being guarded by heavily armed soldiers, it is guarded only by Maremma sheep dogs. A close look at the hillside today will reveal countless pieces of shrapnel as a subtle reminder of the violence that once interrupted this tranquil place.

And “The Rock” continues its silent watch as time marches by.

It is also said that the name Sasso di San Zenobi commemorates a meeting that took place between Saint Zenobius (the bishop of Florence) and Saint Ambrogio (the bishop of Milan) along the via Flaminia near the famous rock sometime around the year 400AD. Every year on the first Sunday of July, local residents hold a religious feast at Sasso di San Zenobi to commemorate this meeting. The 2003 celebration is shown below.

I would like to extend a very special thanks to Roberto Grilli of San Benedetto del Querceto and his father Giorgio for the painstaking research they conducted in honor of all the men who fought in this battle.

Campaigns | Cecina | The Rock | Verona

Back to Top of Page

Researched and Written by Robert J.Holt

Page Content Copyright 2003 - 2026 Robert J. Holt

All Rights Reserved